In a year when artificial intelligence spending has begun to resemble a national infrastructure program, Celestial AI has chosen to stop being a standalone startup. Preet Virk, the company's co-founder and chief operating officer, says the decision to sell to Marvell was less about scale for its own sake than about physics, efficiency, and timing.

Celestial AI has signed a definitive agreement to be acquired by Marvell, a deal expected to close in the first quarter of 2026. Until then, the two firms remain legally separate.

Credit: Celestial AI

Yet the logic of the pairing, Virk argues, is already clear. AI capital expenditure, he notes, is approaching 3% of US GDP, a level seen only in exceptional historical moments such as the railway boom or the mobilization of industry during the Second World War. Hyperscalers are no longer merely buying accelerators; they are constructing what he calls "AI factories, systems designed to produce tokens at an industrial scale.

Idle compute: the 70% problem

The problem is that these factories are deeply inefficient. Model flop utilization for leading models remains below 30%, meaning that roughly 70% of expensive compute assets are idle, waiting not for instructions but for data.

In Virk's telling, this is where Celestial AI fits. Marvell already brings networking, security, and digital signal processing. Celestial supplies the missing interconnect that binds those elements into a coherent, high-utilization system. The two portfolios, he says, are symbiotic.

Photonics at the core

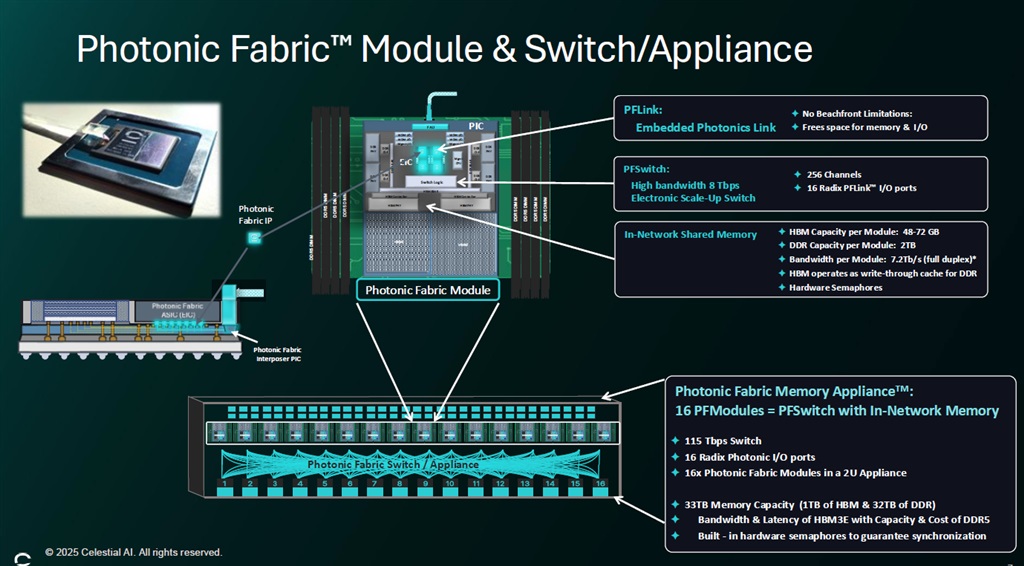

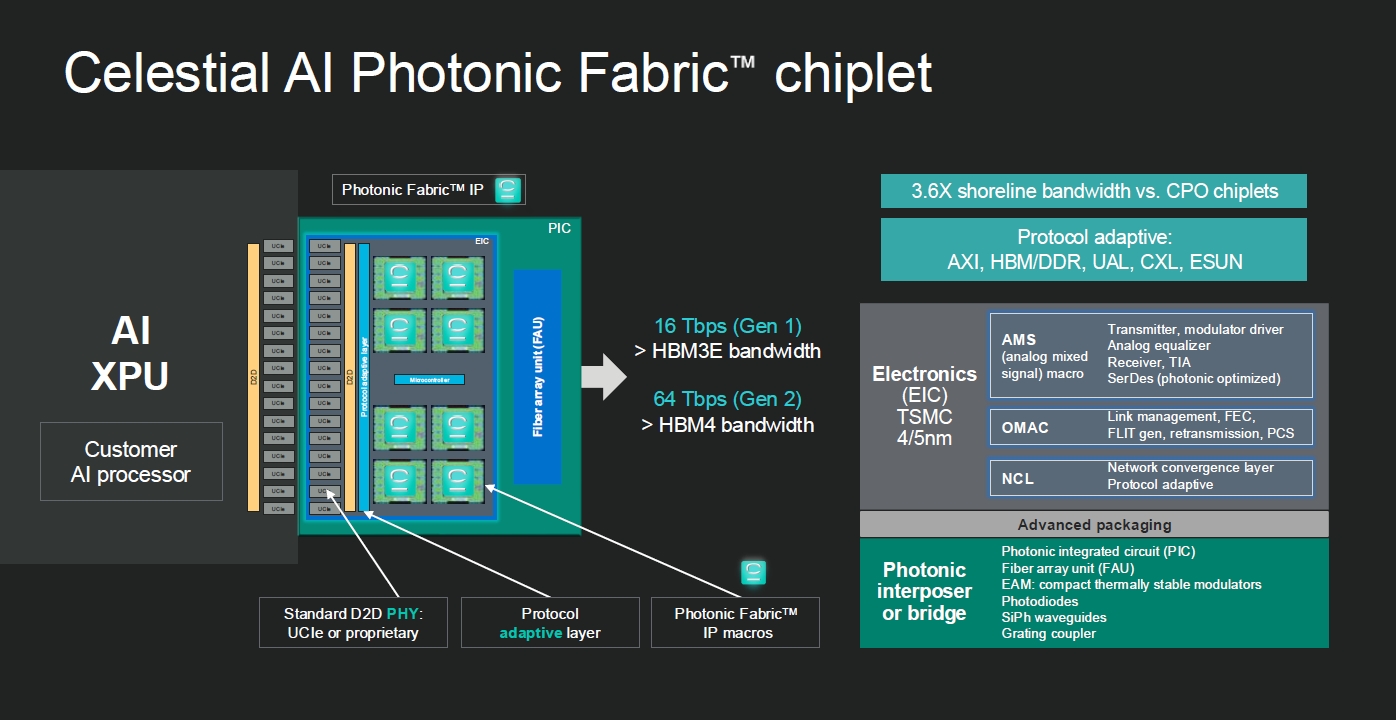

At the heart of Celestial's approach is what it calls a photonic fabric, built around what Virk describes as the world's first chip to place optical input and output in the middle of the die rather than along its edges.

Conventional designs treat the periphery of the chip as "beachfront property" for I/O. By moving optics into the center, Celestial frees the edges for DDR, HBM, PCIe, and CXL controllers. The result is an optical memory appliance capable of attaching up to 33 terabytes of memory to an XPU with a full return-path latency of under 200 nanoseconds.

This matters, Virk argues, because generative-AI reasoning models are asymmetric in their demands for compute and memory. Customers often buy more accelerators than they need simply to gain access to additional high-bandwidth memory. Optical attachment allows memory to scale independently, improving utilization and lowering overall system cost.

Credit: Celestial AI

Four scales of connectivity

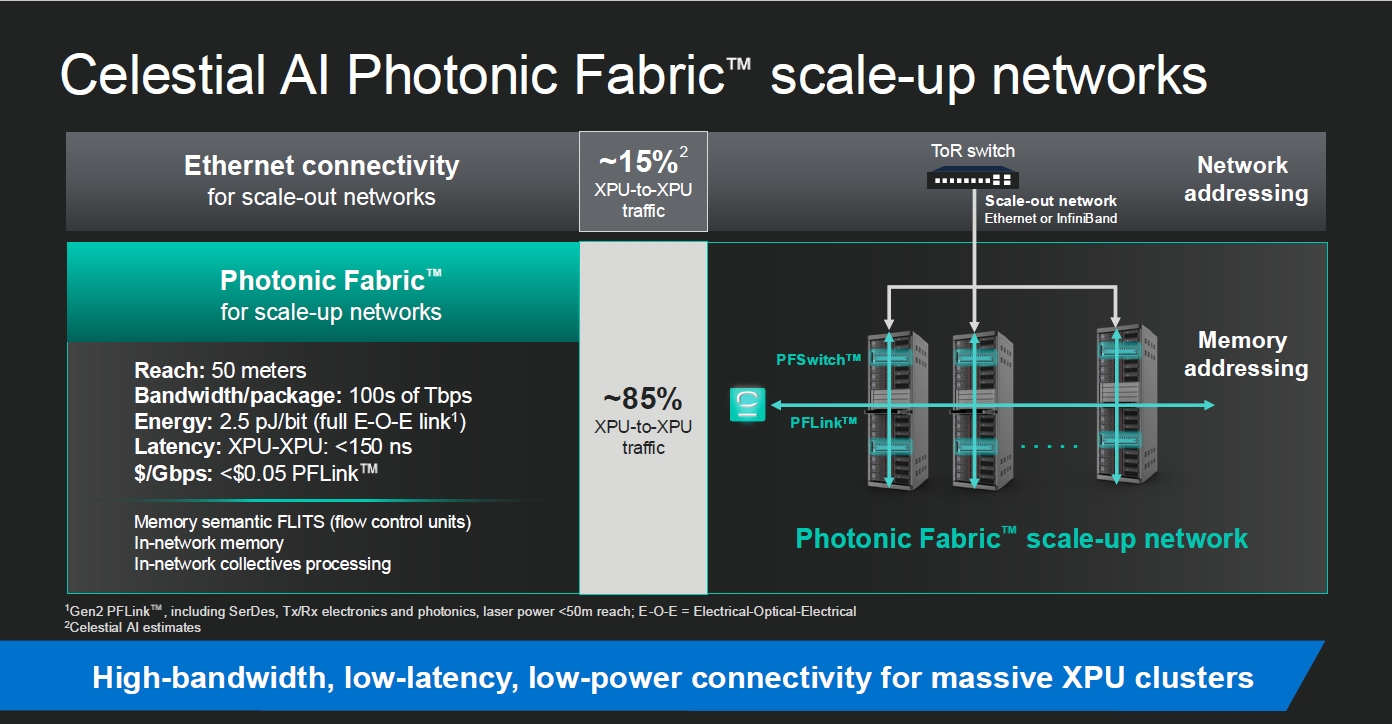

Celestial frames its technology across four distinct "scales" of connectivity. At the smallest level, scale-in refers to links within a single package. Because Celestial's modulators can tolerate the heat inside advanced packages, up to ten dies can be optically tied together.

Scale-up covers the connection of thousands of GPUs across multiple racks, distances that copper struggles to span beyond a few meters. Celestial's optics can reach roughly 50 meters.

Scale-out describes pod-to-pod connections via Ethernet switches, an area of established strength for Marvell. Finally, scale-across links multiple data centers through high-bandwidth optical pipes.

Power efficiency as differentiator

Power efficiency is the company's central differentiator. Celestial's interconnect operates at around 2.4 picojoules per bit, compared with roughly 6 to 7 picojoules for close competitors.

In large-scale systems, the difference is starker. Scale-up operations using copper and NVLink can consume around 53 picojoules per bit. Celestial claims to achieve the same function for less than 15.

Credit: Celestial AI

Virk points out that more than half of a data center's energy budget is now spent moving data rather than performing computation. Cut that cost, and the same facility can produce roughly twice as many tokens.

There is also, he says, a hard limit imposed by physics. Copper interconnects will eventually stall, likely around NVLink generations with 144 or 172 lanes. To tie together a thousand GPUs, optics are not optional but inevitable.

Thermal stability through design

One of the technical hurdles in bringing optics inside advanced packages is heat.

Multi-kilowatt systems generate dynamic thermal conditions that destabilize many optical components. Celestial avoids micro-ring modulators, which are sensitive to temperature fluctuations, and instead uses electro-absorption modulators.

These are thermally stable, comparable in size to micro-rings, and can be placed close to their drivers. The proximity reduces capacitance and power consumption, while allowing the modulators to respond as quickly as the ASIC's temperature changes.

Manufacturing and packaging

On the manufacturing side, Celestial's electrical ICs are built on TSMC's 4 or 5-nanometer process. TSMC invested in the company through its VentureTech arm after concluding that the approach was genuinely distinctive. With Marvell's backing, Virk expects an even closer relationship.

Packaging, he insists, is deliberately unexotic. The company uses standard CoWoS-like flows, supplying its own optical chiplet along with a detailed process "recipe" for fiber attachment. Those recipes, which are patented, are designed to deliver high quality at low cost and are not tied to any single outsourced assembly and test provider. Another patent covers a glass-block lens insertion method that allows the optical components to survive standard over-molding processes.

Credit: Celestial AI

Modular bandwidth scaling

Bandwidth, meanwhile, is scaled by design rather than by fixed product definitions. Celestial's IP macros are compact enough to deliver nearly 1.5 terabits per second per millimeter. Customers can deploy as many as needed to reach aggregate bandwidths of 8, 14, or 16 terabits per second. Wavelength-division multiplexing further reduces fiber count by sending multiple wavelengths down each strand.

Product roadmap

The product roadmap reflects the same modular philosophy. Co-packaged optics for scale-up systems are expected to show results in the second half of 2026.

An optical multi-chip interface aims to make large, multi-die packages appear as a single entity to software. A photonic-fabric network interface card would give conventional servers native optical connectivity. And the memory appliance, built around that 33-terabyte figure, is intended as a rack-level extension of accelerator memory.

Asked about rivals such as Lightmatter or Ayar Labs, Mr Virk declines to engage in point-by-point comparisons. Instead, he points to deployments and customers, and to Marvell's choice. The acquirer, he says, examined the field and selected Celestial, a decision he characterizes as a vote of confidence rather than a marketing claim.

(This interview was conducted with contributions from Tony Huang, Aaron Chen, and Ashley Huang of DIGITIMES Research.)

Article edited by Jerry Chen